Empowering Nepali elderly women: A vibrant community group bridges gaps in healthcare access and communication

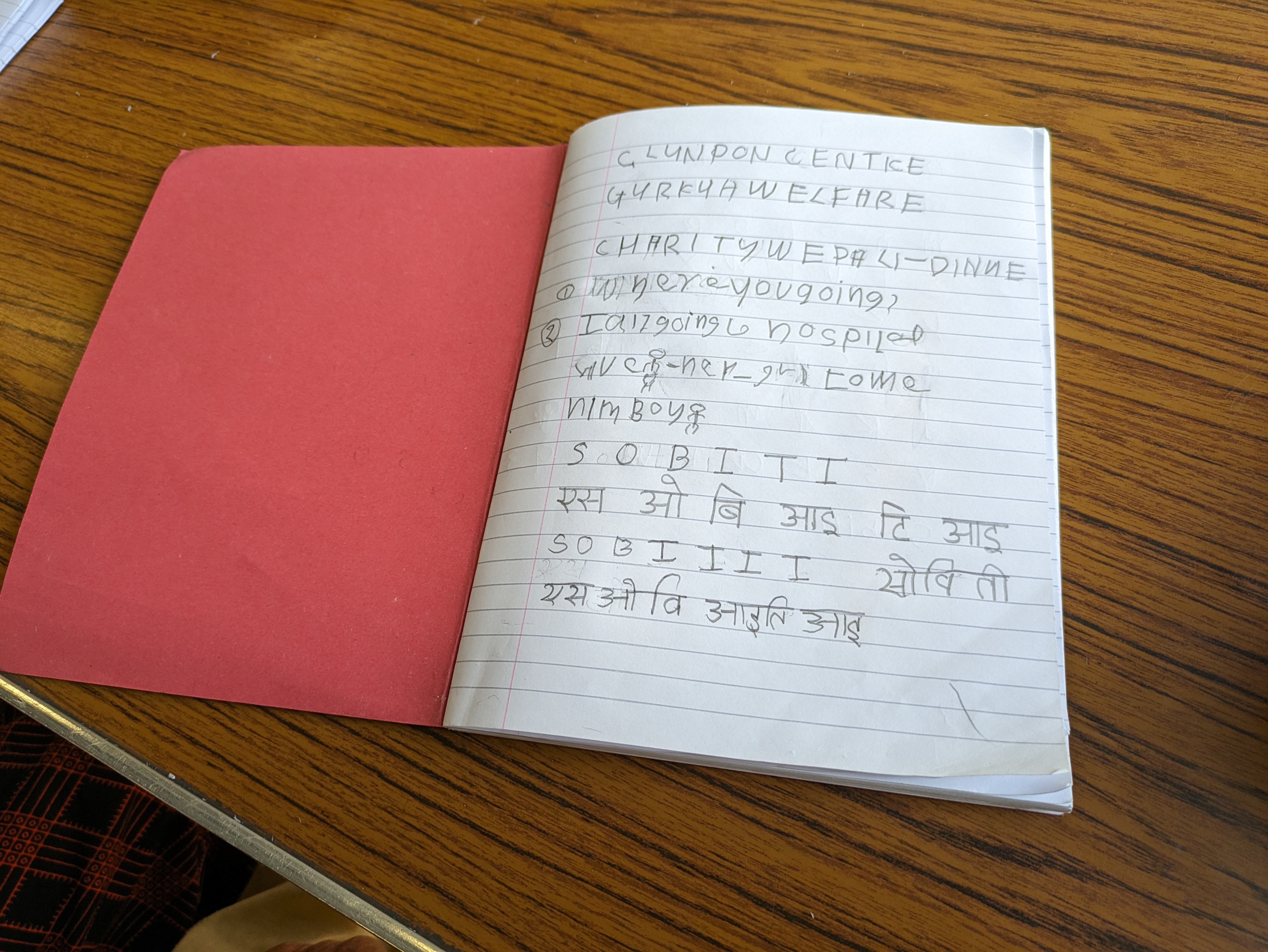

As the clock strikes 12 PM on a Tuesday, the Glyndon Community Centre comes to life, eagerly welcoming its cheerful weekly visitors. Draped in colourful Nepali traditional outfits, more than 40 women—many of them in their 60s and 70s—enter the centre and choose their favourite seats in the main hall.

Before long, the hall, peacefully nestled between the calm of Plumstead and the liveliness of Woolwich, fills up with laughter and happiness as they share stories from the past week. Sita Devi Ghale, a regular attendee, prefers the last row. “The moment I leave here, I start counting the days until next Tuesday,” Sita tells me. “Without this gathering, I might spend the whole day sleeping and doing nothing. Here, I can talk with my friends and learn new things.”

For numerous elderly women like Sita, this weekly get-together of Greenwich Nepalese Gurkha Community is a highlight they eagerly anticipate. It’s a hub for friendship, communication, sharing worries and emotions, and staying connected to their Nepali heritage. “We sing and dance. We have so much fun here and learn a few things too,” says Purna Gurung, another member of the group.

Without this gathering, I might spend the whole day sleeping and doing nothing. Here, I can talk with my friends and learn new things.

However, outside this group, with limited English, Purna and her friends face difficulties in daily life. “My pharmacy people did not give me the main medicine. I had to visit them three times,” Jit Kumari Limbu, 72, told me. “Whenever I go to either GP or pharmacy, I tell them I can’t speak in English. I think that makes it difficult for me.” Sita pulls me to a corner and shares her experience of visiting her GP. “I broke my leg in Nepal, so I had to stay there for several months. When I came back, I had brought three months of medicine with me,” says Sita. “When I ran out of medication, I contacted the GP and pharmacy, but they did not give me any medicine. Instead, they asked me where I had been for so long. I have faced difficulties even for my diabetes medicine. They only gave tablets but no injections.”

Gyan Tamang, the leader of this community group, receives 30-35 calls on busy days supporting community members with urgent needs. According to Gyan, the main challenge for elderly Nepalese trying to access health and care services in the UK is communication, and not being offered access to translation services. “Having interpreter at GPs and hospital could largely improve the situation,” said Tamang, a retired Gurkha who served the British forces for 22 years, before starting this group back in 2013. “Whenever I can I accompany them to GPs, hospitals or even bank or anywhere or even make calls on behalf of them. At times, I feel intense pressure catering to all of them. But I feel happy to be available for them.”